|

History

of Oldbury, Langley and Warley

|

||

|

Communities

of the West Midlands

|

||

|

The

website of Langley Local History Society - Oldbury Local History

Group - Old Warley Local History Society

|

||

|

||

| HOME | |

| NEWS & EVENTS | |

| HISTORY SOCIETIES | |

| PUBLICATIONS | |

| GALLERY | |

| QUESTIONS | |

|

article 007 BASKET MAKING IN OLDBURY |

|

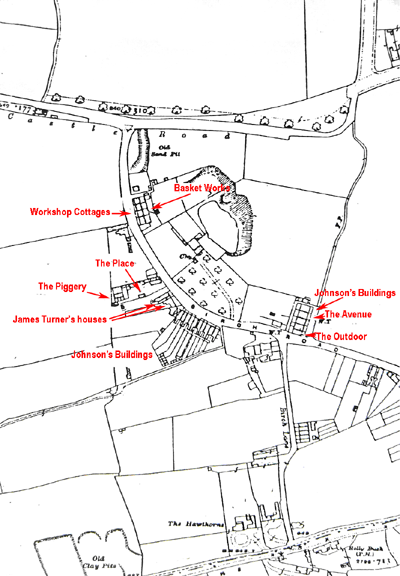

Coming to Warley Some time during the 1850s James Turner, son and grandson of wicker workers of Oakthorpe in Derbyshire, left his village and migrated south to Birmingham. In the 1851 census he is a 13-year-old basket maker, and by the next census (1861) he is married with a toddler and a baby. Mary Ann Morley would bear him fourteen children, six of whom would die in infancy. All surviving boys learnt their father's craft in Irving Street and Upper Gough Street, Birmingham. From Nuneaton and its crowded Abbey Street, Joseph and Maria Johnson, together with their seven children, likewise migrated to Birmingham about 1866; two years later Maria was a widow - she was pregnant and had five children still at school. The two older boys were working in the brass industry but life must have been desperately hard for her. Nevertheless within a few years Johnson's Fruit Market in Sherborne Street was established and the business would remain for the best part of a hundred years. Her grandchildren have told me of the fun their mothers had being pushed in the cart as groceries were bought from the wholesale markets around Horsefair; I guess the return trip was less fun. By the 1880s, after twenty years in the confines of old Ladywood, the Johnsons again got itchy feet. Charles Henry Johnson, the eldest son, had inherited property in Nuneaton and was a successful businessman. He was on the lookout for greater possibilities beyond the city boundaries. Already owning several houses in Ladywood, he managed to acquire a row of brickmakers' cottages in what is now Kenilworth Road off Birch Road, near to where the Wolverhampton Road meets Hagley Road West. It is tempting to say ‘just below the Warley Odeon’ but that would make little sense to anyone under 40…

The Basket Business

The workshop was on the ground floor. Through stable doors three or four workmen would be sitting on the floor, and inclining away from them would be a flat baseboard in the centre of which was a metal spike, perhaps 3 inches in length. The spike was shiny and polished through continual running contact with the willow as the basket was turned while the men threaded the softened willow through the uprights. In the air was the characteristic smell of the craft, a pleasant, earthy smell.

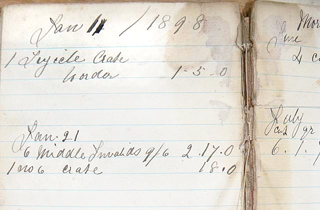

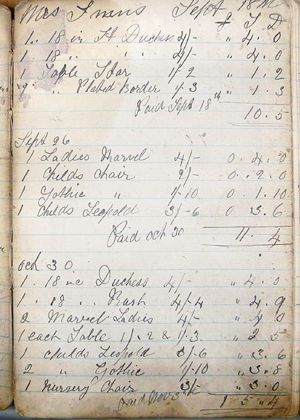

Rabbit hampers were larger and more substantial than the fruit pots with a very heavy border approx. 2ft 6in x 2ft x 1ft 9in, [75 x 60 x 55 cm] with two 1.5in [4 cm] diameter hazel poles fixed under the border across the length of the hamper about 6in apart and 6in [15 cm] from the side border. Dead rabbits were tied together by their hind legs and hung over the poles so that their heads hung down just above the bottom of the hamper. Doreen remembers in the days when greengrocers used to sell their wares from horse drawn carts in the streets and seeing rabbits being offered for sale carried in wicker hampers. Boiling of the willow was carried out in the yard next to the workshop in a large tank which had to be filled each time with fresh water from an adjacent hand operated pump. I and, before me, your Dad were frequently the motive power for the pump." I cannot add much to this except that cycle baskets, mainly made for the Co-operative Society to very exacting measurements, were very much part of the business at the turn of the century, and that in 1922 the men produced about 30 rabbit hampers per week for which they received 1/9 each. [The purchasing power of 1/9 is equivalent to about £3.30 today.] The baskets were not only sold in Birmingham Market, for many firms from Smithfield bought rabbit hampers in baffling numbers: in January 1929 one hundred and forty-seven hampers were sold. Considering how little representation rabbit meat has in the modern diet these numbers are very surprising. Depending on how many were bought, the hampers were sold from 3/8 to 4/- . A basket would be sold for at least twice these prices and more than a pound for the larger laundry baskets.

On the death of James Charles Turner in 1981 the traditional craft of the willow, the craft followed for at least five generations, died with him.

Peter C Turner, BA, Halesowen

References and notes

This article © Peter C Turner 2009 - contact for permission to reproduce |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||